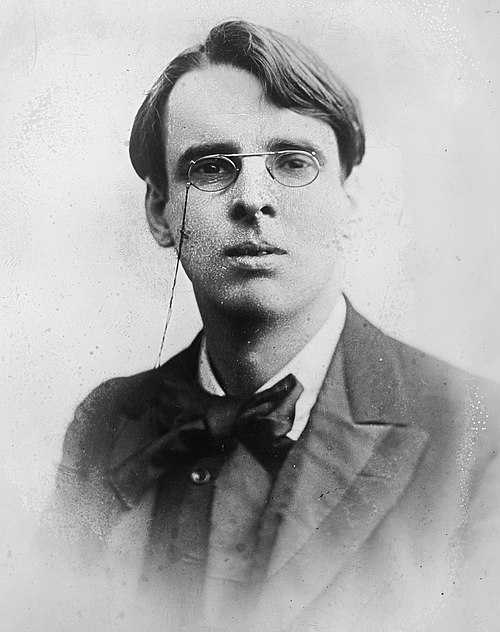

Yeats, William Butler

Yeats is sometimes, misguidedly, defined by his lifelong infatuation with a woman, Maud Gonne, who rejected his proposals of marriage on at least four occasions. He then proposed to her daughter, and was again rejected. These biographical details convince many casual readers that Yeats was clearly an ineffectual aesthete whose art arose from his personal failings. This view of Yeats, however, as a tortured artist blind to how ridiculous he appears to other people misses the greatness of Yeats’ work which arises because he is all too aware of how ludicrous he appears to others . His poems are laden with self mockery, poking fun at his own pomposity. In Broken Dreams, for instance, he becomes the ‘poet stubborn’ writing of Maud’s beauty when ‘age might have chilled his blood’.

My first experience of Yeats was during my first English Literature A Level class: the very first text we were given was Leda and the Swan. I remember Mrs Smallwood asking my class what we thought the poem was about. Well, I read it through twice and was immediately struck by, firstly, the power of the language and, secondly, the horror of what was happening. The rest of the students were looking blankly at the poem so I struggled to explain what I thought was happening, although I was shocked by what I read: a woman was being violently raped by a swan. Over the years I have come back to the poem and I now realise that the shock is not the act of rape itself, but the suggestion that Leda may be complicit in it, that her ‘vague fingers’ may not want to push Zeus from her ‘loosening thighs’. It is this courage to look with unflinching honesty at the difficult, complex and, sometimes, very uncomfortable truth that characterises Yeats’ work.

Yeats was not afraid to say publically when he was wrong or when he didn’t have an answer. Easter 1916, possibly his most famous poem, and certainly one of his most oft quoted, begins with an acknowledgement that he was mistaken to scorn the leaders of the uprising and ends with his failure to explain the significance of the event beyond his belief that a ‘terrible beauty’ had been born. Through exposing these frailties and accepting that he has no more answers than his readers, but doing so with a mastery of structure and language of exquisite power, makes him to Irish literature what Shakespeare is to English literature.

Should we be grateful that Maud Gonne still rejected Yeats even after their one night of consummation? If she hadn’t she would not have been his unobtainable Helen of Troy and we would not have that rich vein of mythology, complexity and longing which marks the greatness in his poetry. His logic may sometimes have been inconsistent; his ideas may, at times, have been bizarre; and some of his greatest poetry may have arisen from a misguided obsession but there is no doubting the power of his writing.