Williams, Tennessee

With the exception perhaps of Arthur Miller, Tennessee Williams was the greatest American playwright of the mid twentieth century. He rose, however, from inauspicious beginnings. Born as Thomas Williams in Mississippi in 1911, he was a sickly child, suffering periodically from diphtheria and provoking the ire of his father, a violent alcoholic who despised what he considered to be his son’s weakness. Owing to the fact that his father was a travelling salesman, Williams’ childhood was further disrupted by the frequent relocations undergone by his family. This sad and troubled upbringing was, many believe, the foundation for the tragic family dramas contained throughout his work.

While at college in Missouri as a young man, Williams saw a production of Henrik Ibsen’s Ghosts and decided that his calling was as a playwright. He was later forced to drop out of college by his father to help support the family by working in a shoe factory; although Williams hated the factory work, he met a fellow worker there who became the basis for perhaps his most famous literary creation, Stanley Kowalski.

After a decade of struggling in menial jobs and battling nervous breakdowns, Williams enrolled in the University of Washington, St Louis, and later the University of Iowa, where he would finally complete his undergraduate English degree in 1938. Throughout this time, he had continued to pursue his dream of becoming a writer, and in 1939, using funds from a grant given to him by the Rockefeller Foundation to develop his talent, he moved to New Orleans, where he worked as a copyist for Franklin D Roosevelt’s Works Progress Administration programme that had been designed to help people still suffering from the effects of the Great Depression. It was at this time that he changed his name to Tennessee, the reasoning for which, strangely enough, was that his father had been born there.

Five years later, Williams’ first major play, The Glass Menagerie (1944), opened in Chicago to positive reviews. The play features a mentally ill character called Rose, who was based on the tragic life of his own sister, who had been subjected to a lobotomy the year before and would subsequently never escape mental institutions for the rest of her life. This decision of Williams’ parents to lobotomise Rose prompted Williams to sever all ties with them.

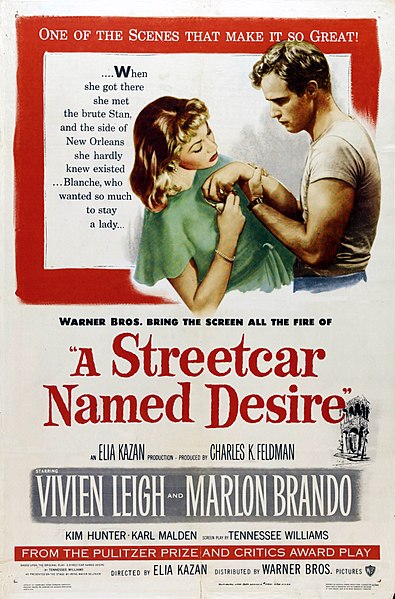

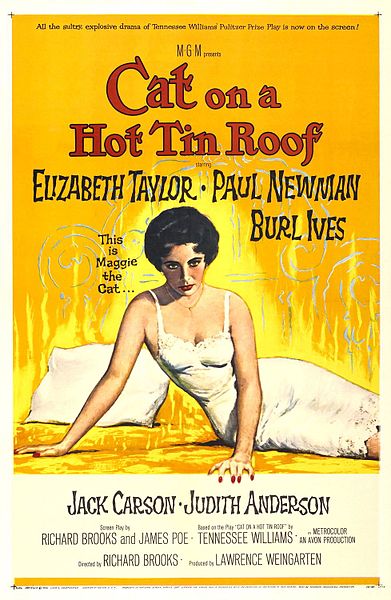

Over the next 10 years, Williams wrote a string of successful plays, including A Streetcar Named Desire (1947) and Cat on a Hot Tin Roof (1955). Set in New Orleans, Streetcar is perhaps Williams’ most well-known play, due in no small part to the titanic struggle between the characters of Blanche DuBois and her terrifying misogynistic nemesis, Stanley Kowalski. These two plays were particularly significant because of their adaptation into films directed by the renowned Elia Kazan. This development meant that Williams’ work reached a wide audience for the first time and established him as one of the foremost literary figures in the American twentieth century. During this period he was also in a homosexual relationship with a man called Frank Merlo, who accompanied Williams on his many travels around the world. Splitting their time between Manhattan and Florida, Williams would later remark that these years with Merlo were the happiest of his life.

In 1963 the pair separated and, a few short months later, Merlo died of lung cancer. This trauma, coupled with Williams’ failure to reach the stratospheric heights of his work during the 1940s and 1950s, caused him to relapse into the bouts of depression and anxiety that had plagued him as a young man. In a tragically ironic turn, Williams became addicted to the very amphetamines that been prescribed to treat his depression, and his literary output steadily diminished in quality. The plays that he did produce, such as In the Bar of a Tokyo Hotel (1969), Small Craft Warnings (1973) and The Red Devil Battery Sign (1976), were all critical and box office failures that exacerbated his weakened mental state.

At the age of 71, Williams was found dead in his New York hotel room having accidentally inhaled and choked on the cap of a bottle of nasal spray. In the decades following his death, Williams has posthumously received a string of awards and honours, including a plaque in the American Poets’ Corner at the Cathedral Church of St John the Divine in New York. Despite Williams’ wish to be buried at sea, his family chose to lay him to rest in the Calvary Cemetery of St Louis, Missouri, determining and shaping the trajectory of his death just as they had his life.