Owen, Wilfred

Wilfred Owen was born on 18

th March 1893 in Oswestry, Shropshire, close to the Welsh border. The house where he was born, Plas Wilmot, belonged to his grandfather. His family seemed to be comfortably off; however, the death of Owen’s grandfather and subsequent sale of the house proved otherwise. Owen was four years old when the family was forced to move from their home, resettling for a short time in Birkenhead, where his father found work with a railway company. Another move later that year after his father’s job was transferred saw Owen relocate to Shrewsbury, where his parents named their new home Wilmot House after the home that Owen had been born in. The Owens moved again in 1900, back to Birkenhead, and then again in 1907, back to Shrewsbury, where they lived in a number of houses before settling.

After finishing school, Owen was accepted to study at the University of London; however, he hadn’t achieved the top grades needed for a scholarship and his parents couldn’t afford the fees. Instead, he became assistant to a Reverend, spending a lot of time with people who were sick, homeless, elderly and illiterate. He had a lot of empathy and compassion for their suffering, something we can see later in his attitude to war and in his poetry. He became very sick due to living in damp conditions and returned home to recover. It took eight months for him to be well enough to work again, this time as a tutor in France. Owen was still in France at the beginning of World War I. He considered joining the French army; however, he returned to England a year after the start of the war to enlist. He joined up on 21

st October 1915, when he was 21 years old. Despite his initial hesitation to enlist, Owen had said, ‘After all my years of playing soldiers, and then of reading History, I have almost a mania to be in the East, to see fighting, and to serve’. This attitude was to be short-lived.

Owen experienced the real nature of war in January 1917, when he wrote to his mother, ‘I can see no excuse for deceiving you about these four days. I have suffered the seventh hell. I have not been at the front. I have been in front of it’. As well as being on the front line, Owen visited the war hospital, writing about and drawing the horrors he witnessed. Owen kept in regular contact with his mother by letter, giving an honest account of his experiences and his attitudes to war. He also included his poems in his letters. On the 19

th January 1917, not long after arriving at the front line, he wrote, ‘The people of England needn’t hope. They must agitate’.

Read more of Owen’s letters to his mother here.

After being caught in the blast of a mortar shell and coming round from being unconscious lying amidst the remains of one of his fellow officers, Owen was sent to Craiglockhart Military Hospital in Scotland with shell shock. In a letter to his mother he wrote, ‘Do not for a moment suppose I have had a breakdown, I am simply avoiding one’. We see Owen’s spirit in this quotation. Owen wrote about war from his experience, drawing upon his empathy and compassion, and using his passion for the writer’s voice in order to speak up. He says, ‘I came out in order to help these boys – directly by leading them as well as an officer can; indirectly, by watching their sufferings that I may speak of them as well as a leader can’. It was his time spent at Craiglockhart that was to have a significant impact on his poetry.

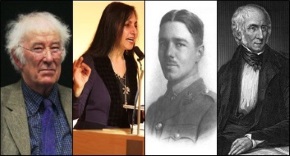

Owen started writing poetry during a holiday to Cheshire when he was 10 years old. He said, ‘I was a boy when I first realised that the fullest life liveable was a Poet’s’. He was particularly inspired by the Romantic poets Wordsworth and Keats. Owen’s poetic style was to change significantly later on, moving from the Romantic to the realistic as he described his experiences of war. The primary influence on Owen’s poetry was his friendship with fellow war poet Siegfried Sassoon, whom he met at Craiglockhart Military Hospital. Owen and Sassoon became great friends, and it is clear that Owen’s poetry would not be what it is without this friendship. In fact, manuscripts still survive showing Owen’s poems annotated in Sassoon’s handwriting. Owen was encouraged by his doctor to write about his experiences as part of his therapy. Sassoon helped Owen, introducing him to the use of satire and demonstrating the power of realism. Owen took Sassoon’s style, and, merging it with his own Romantic one, began to create a new style of poetry. As well as telling the truth as he saw it, directly from the front line – he says, ‘All a poet can do today is warn. That is why the true poet must be truthful’ – Owen used aural imagery in a way that hadn’t been seen before in poetry, to great effect. Bringing the horrors of war to those who were not there through honestly brutal visual descriptions heightened by the noise of war through alliteration and assonance, Owen fulfilled his purpose for his poetry. He said, ‘Above all I am not concerned with Poetry. My subject is War, and the pity of War. The Poetry is in the pity’.

‘Dulce et Decorum Est’ and

‘Anthem for Doomed Youth’ both display Owen’s intentions for his poetry, as well as being clear examples of his use of both visual and aural imagery (click the links to watch them). Most of Owen’s poems were composed between August 1917 and September 1918. Only four of Owen’s poems were published during his life; the majority of his work was published posthumously. Sassoon was instrumental in the promotion of Owen’s work, during Owen’s lifetime and after his death.

Owen returned to active service in July 1918. This was a choice Owen made himself, having had the option to stay on home duty. A deciding factor for this choice seems to have been that Sassoon had returned to England after being injured at war. Sassoon wasn’t to return to the front and Owen felt it was his duty to be there in order to continue writing the truth about war in his poetry. A 1920 review of his poems stated: ‘Others have shown the disenchantment of war, have unlegended the roselight and romance of it, but none with such compassion for the disenchanted nor such sternly just and justly stern judgement on the idyllisers’. Clearly his duty was fulfilled.

On the 4

th November 1918, Owen was killed, aged 25. It was exactly one week before the end of the war, within one hour. His parents were informed of his death as the bells were ringing to signal the Armistice. He was posthumously awarded the Military Cross for fine leadership during battle. The inscription on his gravestone is from a quotation from his poetry: ‘Shall life renew these bodies? Of a truth all death will he annul’.

Today, Owen is still known as one of the greatest war poets. His work has inspired films, plays, novels, songs, compositions, and a BBC docudrama.

Watch it here.