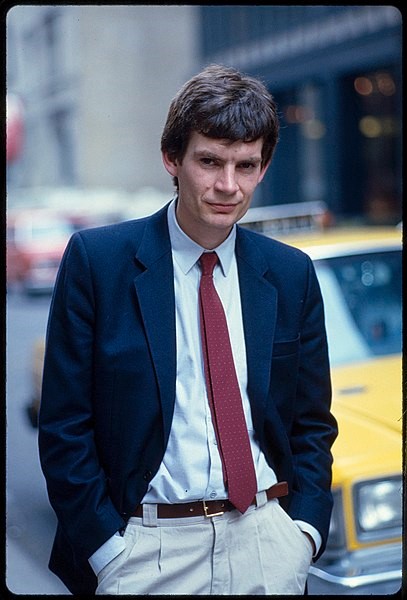

Graham Swift

In 2009 the British Library acquired Swift’s archive. Swift had been reluctant to let his papers go to America. In an interview for The Guardian, written by Maev Kennedy, Swift described the experience of watching his life being driven away from the door of his London home to the British Library, packed into 75 file boxes in the back of a white van, as ‘curiously akin to donating your body to medical science while still alive. There was also an element of feeling I was selling the family silver. Then I thought, well, I'm still alive, and healthy, and working – so suddenly it all felt like a tremendous relief, not having to worry about them any longer, not having to think what would happen to all those papers in the loft if there were a fire or a flood.’

Jamie Andrews, head of modern literary manuscripts at the British Library, wrote that Swift is a very interesting figure because ‘he comes from that generation of writers when the English novel really reasserted itself and regained its confidence and its international stature – yet he stands slightly apart from them in his Englishness and his sense of history’. He added that he thought that Swift would unquestionably be seen as one of the pre-eminent writers of the English post-war period.

According to the British Council website, Swift has an ‘obsession with the reality of history’. This can be seen as central to Shuttlecock (1981), Waterland (1983), Out of This World (1988) and Ever After (1992). In these novels Swift explores the nature of the relationship between personal and public histories, and contrasts orderly narratives and the random nature of real life. For example in Waterland, the history teacher, Crick, interweaves accounts of his own life with events and characters from the nineteenth century onwards. The landscape is also of great importance, as can be seen with the Fens in Waterland: the background is almost a character in its own right.

Further insights into aspects of Swift’s writings appear in an interview with Patrick McGrath for the writers’ magazine Bomb. For example Swift says ‘I wouldn’t be a novelist if I wanted to be a philosopher’; he wants his novels to give readers ‘an experience, not something from which they can extract messages’.

On history:

Swift highlighted the paradox of history, which is constantly confronting the basic choice: ‘Why should we summon up the past? Why should we remember anything, whether it’s personal or collectively? Does it do us any good? Does it hinder us?’ Swift made the observation that the character of Dick in Waterland is a particular embodiment of this paradox.

On superstition:

Speaking about the abortion episode in Waterland, Swift said that superstition is undoubtedly a bad thing: ‘All the potions and the sheer crudeness, the unmedical nature of it all, this has disastrous consequences. But in another sense… superstition… is a benign thing; even telling stories is a kind of superstition, an imposing of extra structure on reality, and it’s something very much needed by these people, who happen to live in a landscape which almost says to them, look, reality is flat and empty. And all you can do in life is make something, and insofar as superstition is creative, it’s perhaps no bad thing.’

On integrating non-narrative, non-fictional material into the story:

Swift said that he rather relished in making the reader perplexed when, say, in Waterland, readers read a narrative chapter and then turn to something ostensibly not connected, for example a chapter about eels, leaving them rather bemused.

On magical fiction:

When referring to magical realism Swift said it was important that fiction was magical, as well as looking really hard at the real world, and that he has certainly been influenced by writers such as Garcia Marquez (One Hundred Years of Solitude, Love in the Time of Cholera) and has found their writing very stimulating. In Waterland an example of this would be when a live fish drops into Mary’s lap, and, following local superstition, it turns out that she is barren.

On writing:

In the interview Swift confirms that writing is solitary work: ‘I think in the end writing is a lonesome business. You have to go away by yourself to do it, whether you’ve got hundreds of friends or not. Nothing will ever change that.’

© ZigZag Education 2026: content may be used by students for educational use if this page is referenced.

| 1949 |

Birth

|

||

| 1960s |

Education

|

||

| 1981 |

Publication of Shuttlecock

|

||

| 1983 |

Publication of Waterland |

||

| 1983 |

Geoffrey Faber Memorial Prize

|

||

| 1983 |

Best Young Novelist Award

|

||

| 1992 |

Waterland adaptation

|

||

| 1996 |

Publication of Last Orders

|

||

| 1996 |

James Tait Black Memorial Prize

|

||

| 2009 |

Swift’s archive

|

||

| 2021 |

Mothering Sunday adaptation

|