Gilman, Charlotte Perkins

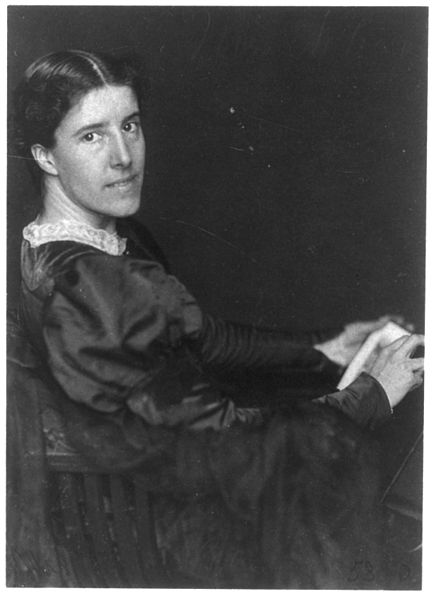

Charlotte Perkins Gilman was born on 3rd July 1860 in Connecticut. Her mother, Mary Perkins, was advised by a physician that she could die in childbirth if she went on to bear further children, and so Charlotte had only one other sibling, a brother named Thomas Adie who was just over a year older than herself. Charlotte faced poverty from an early age as a result of the abandonment of her family by her father Frederick Beecher Perkins in her infancy. This had not only a significant financial effect on the family but a severe emotional one too. Mary forbade her children to form emotional attachments to their peers or to read fiction with the hope of protecting them from the hurt she had experienced at the hands of her deserting husband. To a similar end, Mary avoided emotional expressions of affection towards her children; in her autobiography, Gilman recalls her mother only behaving lovingly towards her when she thought that her daughter was asleep. Charlotte found this approach very difficult and records her frequent attempts to remain awake but feign sleep in order to experience the affection that she so desired from her mother.

Her mother’s inability to financially support the family alone led to the frequent presence of Gilman’s paternal aunts, Isabella Beecher Hooker, Harriet Beecher Stowe and Catharine Beecher, in her childhood. Isabella was a suffragist, and so it is significant to note the active presence of disillusionment with the position of the female within contemporary society as part of Gilman’s childhood.

Despite her mother’s instructions regarding fiction, Gilman combated the loneliness and isolation of her childhood through frequent visits to the public library. She taught herself to read at the age of five when her mother was ill, and this was the beginning of a lifelong love of and interest in literature. Although she was a poor student at school, she had a striking natural intelligence and also a wide reach of knowledge gleaned from private study. She attended seven different schools, but only studied formally until she was 15. At age 18 her absent father supported her financially to enrol in classes at the Rhode Island School of Design. She went on to become financially independent as a trade card artist, painter and tutor.

Gilman spent four years in a loving relationship with a woman called Martha, an old friend who offered her the affection and intimacy that she had craved throughout her childhood. However, Martha had very traditional views regarding marriage and ultimately left Gilman to take a traditional marital role with a man. She met the artist Charles Walter Stetson around the time of this loss in 1882, and after two years of being pursued by him she reluctantly agreed to marry him in 1884, giving birth to their daughter Katherine Beecher Stetson the following year. Gilman was predisposed to depression and experienced severe post-partum depression following the birth of her daughter. However, this was dismissed by physicians as being nothing more than typical ‘nervous’ and ‘hysterical’ tendencies that, in the nineteenth century, were perceived as natural afflictions related to femininity and being a woman. The pressures of marriage and motherhood led to this developing into a powerful depression that progressed as far as the expression of suicidal desires recorded by her husband in his diaries. She became so debilitated as to be unable to leave her bed, talk or feed herself. There was a strong belief in the nineteenth century that this kind of behaviour in a woman was the result of what was seen as an ‘unnatural’ involvement in intellectual pursuits and disconnection from domestic life. She was given the typical Victorian treatment of ‘rest cure’, whereby the patient is confined to a bed and prevented from engaging in any kind of mental or physical activity at all for a period of several weeks. After nine weeks, Gilman was discharged from her treatment but ordered to refrain from painting, instructed to strictly limit her intellectual activity and to throw herself into domestic life, particularly motherhood. Her doctor advised her to keep her daughter with her at all times. However, the only notable improvement to Gilman’s mental health came in 1888 when she and her husband separated. They legally divorced in 1894, and Stetson remarried Gilman’s close friend Grace Ellery Channing. Gilman was reportedly happy for the couple and, after a short period of living with her daughter in Pasadena California, she sent Katherine back to the East to live with them. Gilman held strongly progressive views regarding paternal rights, claiming a strong belief in the mutual entitlement of Katherine and Charles to get to know each other and to be involved in each other’s lives.

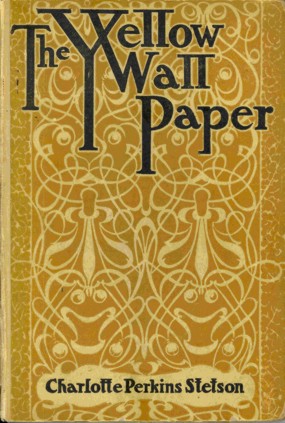

Gilman’s first job was as an artist of trade cards aged 18, the profits of which she used to support classes at the Rhode Island School of Design, along with financial aid from her father. 1890 was arguably the most productive year of her career in literary terms; she wrote a novella, 15 essays and her famous short story ’‘The Yellow Wallpaper’. ’‘The Yellow Wallpaper’ was printed for the first time two years later in the January issue of The New England Magazine. It was extremely popular with the contemporary feminist press and has since been anthologised several times, becoming a significant component within the American literary canon. The story depicts a woman suffering from depression, who ultimately suffers a breakdown at the hands of the misguided traditional Victorian treatment of ‘rest cure’ that she is being subjected to; the story intended to highlight the fallacies of this cure and the wider issues related to women’s social and economic position, as well as their lack of independence and autonomy. The text was a semi-autobiographical account of her own experience of mental health issues, and indeed she sent a copy to Dr Silas Weir Mitchell, the doctor who attempted to treat her own case of post-partum depression with rest cure.

Gilman was also an accomplished writer and lecturer in non-fiction, and, as an activist for social reform, she championed ideas that were far ahead of her time. She argued the importance of practical social reforms such as childcare that allowed women to work outside of the home and kitchen-less accommodation for women to take the focus off the domestic role for women. In her famous work Women and Economics, Gilman highlights the damages against not only women but society as a whole due to the disadvantaged position of women within society, arguing that if women were allowed to work in the same way as men rather than conscripted to domestic servitude as an automatic consequence of their gender, many more women would be happy and fulfilled, and society would benefit from an economic boost due to an increased workforce.

Gilman was also famous writing for and single-handedly producing her own magazine, The Forerunner. She produced 86 issues over a seven-year-and-two-month run from 1909 to 1916. Alongside serialised versions of her own fiction produced for the magazine, Gilman also featured other contemporary writers with a focus on material that she hoped would ‘arouse hope, courage and impatience’. The magazine was produced with a view to offering an alternative to the overly sensationalised mainstream contemporary media. The magazine had nearly 1,500 subscribers and is viewed by scholars as one of her greatest accomplishments.

Following the death of her mother in 1893, Gilman also moved back to the East and contacted her first cousin for the first time in over a decade, a Wall Street attorney named Houghton Gilman. They instantly began spending a lot of time together, and their relationship soon became a romantic one. They wed in 1900 and remained happily married until Houghton’s death from a cerebral haemorrhage in 1934. Gilman herself had been diagnosed with terminal breast cancer in 1932 and, unwilling to let her body deteriorate slowly and painfully, she took her life into her own hands on 17th August 1935, committing suicide via an overdose of chloroform.