Chaucer, Geoffrey

Writing in 1700, the English poet John Dryden termed Geoffrey Chaucer the ‘Father of English Poetry’. While criticising Chaucer’s verse as ‘not Harmonious’, he praised him for his characterisation, his ‘good Sense’ and the fact that ‘As he knew what to say, so he knows also when to leave off’. While we might dispute Dryden’s criticisms of Chaucer’s poetry – which can be attributed to his ignorance of the fourteenth-century English in which Chaucer wrote – the epithet with which he crowned Chaucer seems entirely suitable. A learned man who almost certainly knew French, Latin and Italian, Chaucer nonetheless chose to write all his works in English, a language which in the fourteenth century was still regarded as of low status: it was the language of everyday conversation and interactions, not the language of culture and learning. By writing poetry in English that was read in the highest circles in the land, Chaucer gave English a status that was normally reserved for Latin and French (the languages of the church and the court) and helped create a vernacular literature in this country.Compared to Shakespeare, who lived 200 years after Chaucer and about whom we have very little certain information, we know a surprising number of details about Chaucer’s life. This is principally due to his entrance – at a young age – into royal circles, as a result of which his name appears in a number of records from the time. Born into a middle-class London family of wine merchants somewhere between 1340 and 1345, by the time he was a teenager Chaucer was working as a page to Elizabeth, Countess of Ulster and daughter-in-law of King Edward III. While this was a relatively menial position, it granted Chaucer entry into a system of royal patronage which proceeded to support him – and his writing - throughout his life. He was clearly highly valued by the monarchy and other members of the nobility: King Edward III’s ransom payment of £16 to liberate him from his French captors in 1360 has been estimated as being the equivalent of somewhere between £10,000 and £25,000 in today’s money, a not inconsiderable sum to pay, even for a king! Until his death in 1400 he was consistently supported – financially and otherwise – by the monarchy and nobility, enabling him to lead a comfortable lifestyle and, more importantly, to write.

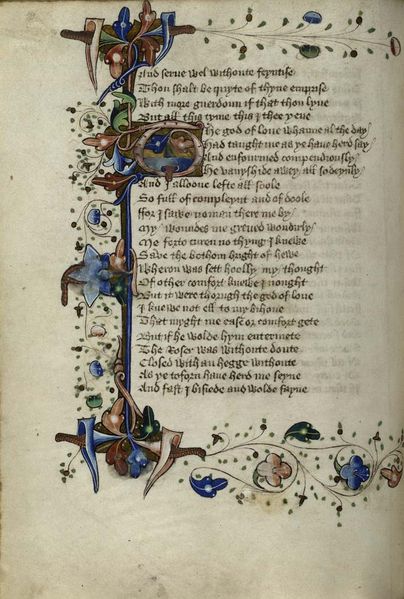

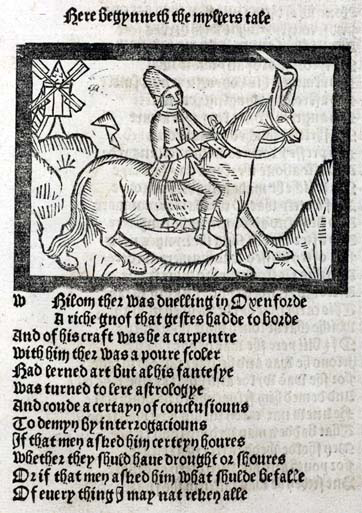

Unlike many writers, who struggle to make a living or find recognition, Chaucer occupied a very privileged position. He had a ready immediate audience for his writing amongst the court, yet he quickly became popular with members of the emerging middle classes and women; his popularity in his lifetime is evident from the number of manuscripts of his work that still survive today: 83 of all or part of The Canterbury Tales and 16 of Troilus and Criseyde; this probably presents a fraction of the number in existence in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. Once the printing press arrived in England, Chaucer’s work was quick to be printed: The Canterbury Tales was the first principal text produced by William Caxton at his printing press in Westminster, and Chaucer’s popularity has never really waned. His achievements were acknowledged from the outset by his poetic contemporaries: Thomas Hoccleve in The Regiment of Princes (c. 1410) described Chaucer as ‘the first fyndere of our fair langage’ and John Lydgate in The Fall of Princes (1430s) referred to him as the ‘lodesterre … off our language’ (a lodestar is a star that is used to guide the course of a ship).

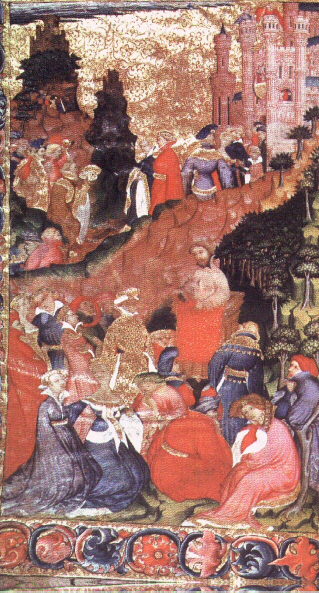

In addition to his elevation of the vernacular to the status of poetic language, Chaucer’s greatness also lies in the range of literary texts he produced: short lyric poems, elegies, dream visions, translations, saints’ lives, tragedies, beast fables, fabliaux (short verse tales, often crude in subject-matter, originally from France) and astronomical treatises. He was the first English poet to use the iambic pentameter (a poetic line ten syllables in length, in which an unstressed syllable is followed by a stressed syllable, and so on), a poetic rhythm later used by Shakespeare. While many critics rate Troilus and Criseyde, his tale of the tragic love story between Criseyde (a Trojan woman) and Troilus (a Greek soldier) during the Trojan War, as his masterpiece, it is The Canterbury Tales for which Chaucer is best-known and loved. Like his Italian near-contemporary, Giovanni Boccaccio (1313–1375), who in The Decameron (early 1350s) used a frame narrative of 10 young people fleeing the plague in Florence and passing the time telling stories (10 stories each over 10 days, resulting in 100 stories), Chaucer also uses a frame narrative in his Canterbury Tales: his is the story of 30 pilgrims (one of whom is called Geoffrey Chaucer), from all walks of medieval society, who to pass the time on a pilgrimage from an inn in Southwark, London to Canterbury, to visit the shrine of St Thomas Becket, the Archbishop of Canterbury murdered during the reign of Henry II, participate in a storytelling competition which is judged by the Host of the inn, Harry Bailey. While Boccaccio’s interest lies principally in the stories that his 10 characters tell, Chaucer’s approach is more sophisticated. A number of his pilgrims are detailed satirical portraits of stock figures in medieval society – the dishonest Pardoner, hypocritical Prioress, fraudulent Miller, lecherous Friar – yet through their voices he grants them an individuality, and often a surprising amount of sympathy. The tales the pilgrims tell encompass a range of genres and subjects (chivalric romances, saints’ lives, fabliaux, beast fables), and there is some very astute matching of teller and tale.

Another feature that makes Chaucer’s writing – and specifically The Canterbury Tales - so fascinating, is his surprisingly (post)modern sensibility. Nowadays we are accustomed to reading metafictional texts – where the text draws attention to itself as a fictional text (famous examples include John Fowles’s The French Lieutenant’s Woman and Ian McEwan’s Atonement), but Chaucer also made use of this device. He revels in the comic potential of such an approach, and nowhere is this more evident than in The Canterbury Tales. The poem opens with 'The General Prologue' in which the pilgrims are introduced, with many of them described in detail by the narrator. This narrator – a fictional Geoffrey Chaucer – is a comic persona: a naïve and simple figure who appears somewhat overwhelmed by many of the characters he encounters - he repeatedly refers to the Knight as ‘worthy’ and adjectives used to describe characters are frequently made into superlatives through use of the word ‘ful’. But Chaucer saves his biggest joke for the storytelling competition when the fictional Chaucer’s first attempt – a verse romance called The Tale of Sir Thopas – is halted half-way through by the Host who complains that his ‘drasty rymyng is nat worth a toord!’ Reading Chaucer both draws us into a deeply unfamiliar world – of religious practices and beliefs, of strange language – and makes us realise how little has changed over the last 600 years!

© ZigZag Education 2026: content may be used by students for educational use if this page is referenced.

Show / hide details

| 1343 |

Chaucer born

|

|

| 1357 |

Chaucer was in the service of Elizabeth, Countess of Ulster, and wife of Prince Lionel, the son of Edward III

|

|

| 1359–1360 |

Chaucer was captured by the French at the Siege of Reims

|

|

| 1366 |

Chaucer married Philippa

|

|

| 1367 |

Chaucer entered Edward III's service as an esquire; he is granted a royal annuity for life of £20

|

|

| 1360s |

Chaucer translated excerpts of the medieval French poem Le Roman de la Rose into the Middle English The Romaunt of the Rose |

|

| 1369–1374 |

Composed his first significant original poem, The Book of the Duchess |

|

| 1374 |

Chaucer received annuities from both John of Gaunt and Edward III

|

|

| 1370s |

In 1372–1373 and 1378 Chaucer made trips to Italy on behalf of Edward III

|

|

| 1374 |

Chaucer was appointed controller of the port of London customs – a post he occupied for 12 years – and a lifelong lease on accommodation in Aldgate

|

|

| 1379–1380 |

Chaucer wrote The House of Fame

|

|

| 1380 |

In a Latin legal document, Cecily Chaumpaigne released Chaucer from any further legal action concerning 'de raptu meo'

|

|

| 1381–1382 |

Chaucer wrote The Parliament of Fowls

|

|

| 1380s |

Chaucer relocated to Kent

|

|

| 1380s |

Chaucer wrote Troilus and Criseyde |

|

| 1386–1387 |

Chaucer wrote The Legend of Good Women

|

|

| 1387–1400 |

Chaucer wrote The Canterbury Tales |

|

| 1389–1491 |

He became clerk of the King's Works

|

|

| 1394 |

Granted an annual pension of £20 by Richard II

|

|

| 1400, 25th October |

Chaucer died

|

|

| 15th century |

Chaucer was honoured posthumously by his contemporaries, the poets Thomas Hoccleve and John Lydgate.

|

|

| 1478 and 1483 |

William Caxton produced the first printed editions of The Canterbury Tales. |

|

| 1532 |

William Thynne edited the first printed collection of Chaucer's works

|

|

| 1556 |

Chaucer's remains were moved to a new tomb in the area of Westminster Abbey now known as Poets' Corner |

|

| 16th and 17th centuries |

Chaucer was the most widely printed English author, and the first to have his works collected in single-volume editions.

|

|

| 1868 |

Frederick James Furnivall founded the Chaucer Society

|

|

| 1900 |

Walter William Skeat established the base text of all Chaucer's works with his one-volume edition for Oxford University Press |

|

| 1966 |

The Chaucer Review was founded

|

|

| 2003 |

The Canterbury Tales were adapted for a modern audience by the BBC

|