Sherriff, R C

Robert Cedric Sherriff was born on 6th June 1896 in Hampton Wick in Middlesex. After attending grammar school, he was employed by the Sun Assurance Company in London as a clerk in 1914. When war broke out, the British Army advertised for men between the ages of 17 and 30 to be junior officers, and Sherriff decided to apply. However, his application was rejected. By 1915 the British had lost so many men they were forced to lower their standards, and in November, Sherriff’s second application was accepted.On 7th October 1916 Sherriff arrived on the front line at the Western Front. On 7th January 1917 he was injured, but after two weeks of treatment returned to the front line. On 31st July 1917 Sherriff was part of a British attempt to break through the German lines at Passchendaele. The conditions during this assault were particularly miserable. Sherriff himself described it as follows:

The living conditions in our camp were sordid beyond belief. The cookhouse was flooded, and most of the food was uneatable... The cooks tried to supply bacon for breakfast, but the men complained that it smelled like dead men.

During the attack Sherriff was injured when a shell detonated nearby, sending shards of concrete into his face. He was taken to a nearby hospital at Wimereux for immediate treatment, and was then shipped back to England, where he remained in hospital until November. Following this, Sherriff joined the Home Service battalion of his regiment, and assisted with the war effort at home until March 1919. For his services during the war, he was awarded the Military Cross.

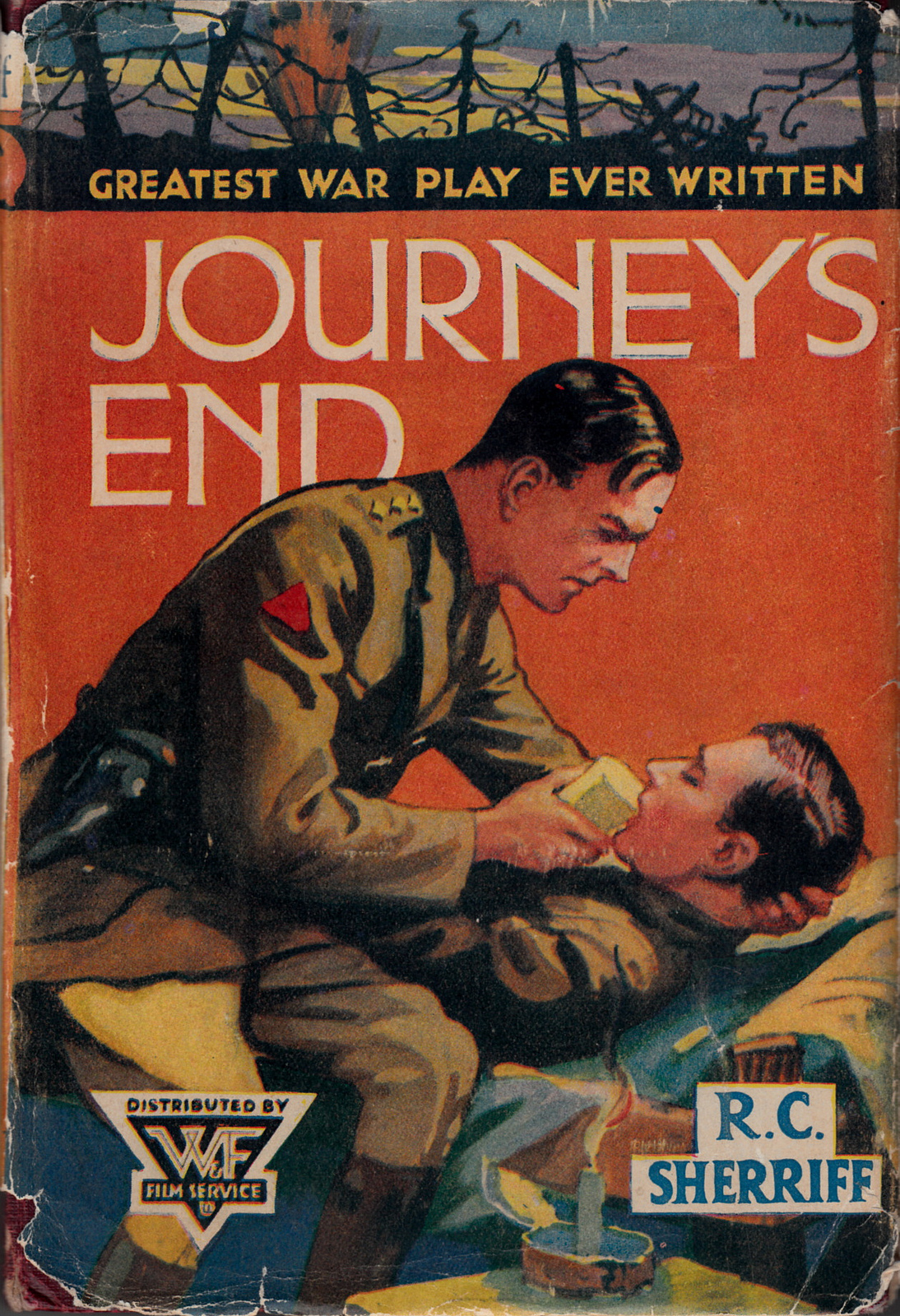

After leaving the military, Sherriff returned to London to work as an insurance adjuster. He began writing plays, of which the seventh was Journey’s End in 1928. In 1931 he went to New College, Oxford, to study History. Following completion of these studies, Sherriff went to Hollywood, and made a career writing screenplays. He won an Academy Award in 1939 for his work adapting Goodbye, Mr Chips for the screen. Sherriff wrote many other plays and film scripts, but Journey’s End is arguably the best known and most critically acclaimed. He died in London on 13th November 1975, aged 79.

Show / hide details

| 1896, 6th June |

Birth

|

|

| 1897–1914 |

Education and boyhood interests

|

|

| 1914 |

Early employment

|

|

| 1914–1917 |

War

|

|

| 1918–1919 |

Return to Britain

|

|

| 1919–1926 |

Writing for the theatre

|

|

| 1928 |

Journey’s End

|

|

| 1930 |

Financial independence

|

|

| 1931–1932 |

Further education

|

|

| 1933–1944 |

Screenwriting and Hollywood

|

|

| 1955 |

Screen, stage and literary writing

|

|

| 1960 |

Musical theatre

|

|

| 1965 |

Loss of mother

|

|

| 1968 |

Autobiography

|

|

| 1928–1975 |

Critical reception

|

|

| 1975, 13th September |

Death

|

|

| 1975–2021 |

Legacy

|